Arcadia Exhibition : Amy Beager, Elizabeth Magill, Freya Douglas-Morris, Hannah Brown, Rene Gonzalez, Saad Qureshi and Sue Williams A'Court

What aligns these artists are not topographical records of the landscape or locations, but evocative, dream-like scenes that create a sense of solace, contemplation, memory and human connection.

The works in this exhibition highlight our profound connection with nature, ever more poignant and deeply felt given recent global events. The exhibition explores diverse artistic representations of landscapes and the environment, and emphasizes the strength and value of our relationship with the natural world, while also hinting at its peril.

What aligns these artists are not topographical records of the landscape or locations, but evocative, dream-like scenes that create a sense of solace, contemplation, memory and human connection.

-

Sue Williams A'Court, Desire and Longing

Sue Williams A'Court, Desire and Longing -

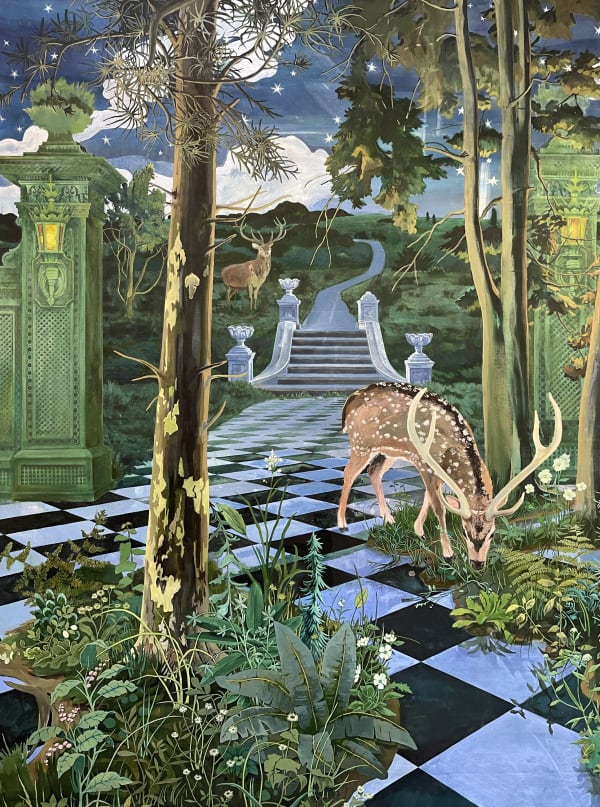

Rene Gonzalez, Deer Gardens, 2022

Rene Gonzalez, Deer Gardens, 2022 -

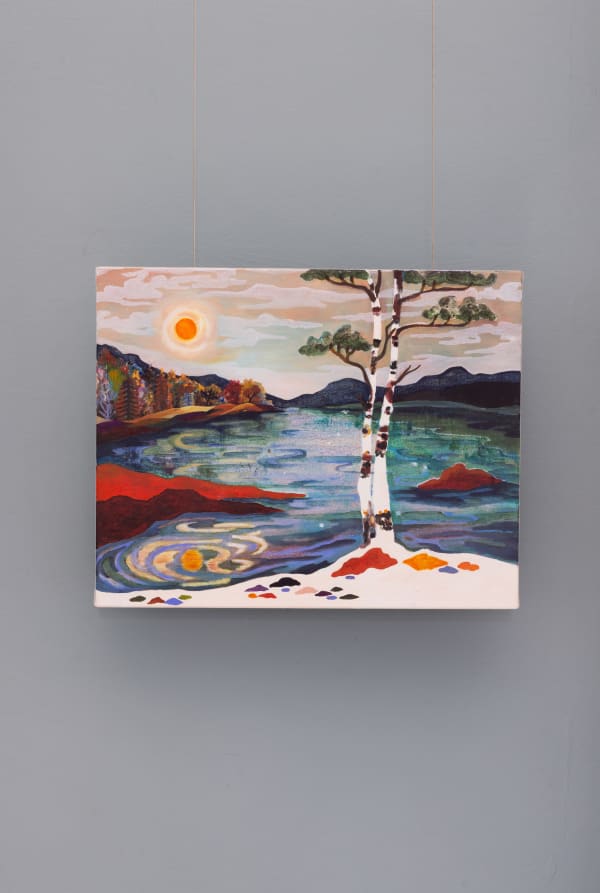

Freya Douglas Morris, Evening Sun, 2021

Freya Douglas Morris, Evening Sun, 2021 -

Elizabeth Magill, Still (Revised), 2017-2022

Elizabeth Magill, Still (Revised), 2017-2022

-

Saad Qureshi, Blue Hour IV

Saad Qureshi, Blue Hour IV -

Amy Beager, Climbers, 2022

Amy Beager, Climbers, 2022 -

Sue Williams A'Court, Desire and Longing (after Mr and Mrs Andrew Gainsbough)

Sue Williams A'Court, Desire and Longing (after Mr and Mrs Andrew Gainsbough) -

Amy Beager, Dream If You Can, 2022

Amy Beager, Dream If You Can, 2022

-

Hannah Brown, Hedge I, 2017

Hannah Brown, Hedge I, 2017 -

Rene Gonzalez, Nothing But a Little Boy, 2021

Rene Gonzalez, Nothing But a Little Boy, 2021 -

Freya Douglas Morris, Stay Bright, 2022

Freya Douglas Morris, Stay Bright, 2022 -

Elizabeth Magill, Fota Park (Red), 2000

Elizabeth Magill, Fota Park (Red), 2000

-

Image courtesy of Home House and Rebecca Hope

-

Image courtesy of Home House and Rebecca Hope

-

Image courtesy of Home House and Rebecca Hope

-

Image courtesy of Home House and Rebecca Hope

“Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.

Meanwhile the world goes on.

Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain

are moving across the landscapes,

over the prairies and the deep trees,

the mountains and the rivers.

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again.

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting –

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.”

Extract from ‘Wild Geese’ by Mary Oliver, Poet, 1986.

Throughout the Western and Eastern canon of art history, depictions of landscapes have been a significant preoccupation for artists, often blending the inner and outer worlds into metaphysical or spiritual scenes that capture our deep connection with the natural world. This exhibition is presented within the beautiful Georgian interior of Home House, designed by renowned architect Robert Adams in 1775. In the eighteenth century, the landscape paintings of Claude Lorrain became highly collected in Europe and their bucolic visions of pastoralism inspired many artists of the time to focus on the genre. It eventually became one of the dominant art forms in the nineteenth century, particularly during the Romantic movement when representations of nature could dramatically and empathetically reflect the human condition. It is this extraordinary tradition of responding to and capturing the natural world that this exhibition seeks to engage, celebrating utopian and idyllic scenes that transport the viewer. The works in the exhibition highlight our profound connection with nature, ever more poignant and deeply felt given recent global events. The exhibition explores diverse artistic representations of landscapes and the environment, and emphasizes the strength and value of our relationship with the natural world, while also hinting at its peril.

The works of Sue Williams A’Court evocatively recall landscape scenes from the past, and she repositions these landscapes in a contemporary context, offering a fresh perspective on the genre. The two works in the exhibition directly reference the works of Georgian painter Thomas Gainsborough, and implicitly reference the idyllic vistas of Claude Lorrain, giving a reverential nod to the past. In ‘Desire and Longing’, the iconic portrait by Gainsborough of ‘Mr and Mrs Andrews’ is appropriated, with the figures noticeably removed from the scene. This absence reinforces the true subject of the work, the English countryside in all its Arcadian grandeur. Williams A’Court deftly weaves the landscape art of the past with a sense of nostalgia and reverence, but also provides a meticulously rendered view of the landscape that encourages pause and reflection; a restorative, meditative process.

Capturing the essence of Arcadia and the Sublime are the exquisite paintings by Freya Douglas-Morris. The artist creates scenes that blend differing landscapes and natural elements to present the viewer with an other-worldly, dream-like vision. Often taking a memory or biographical event as a starting point, Douglas-Morris conjures a terrain that is ambiguous in time and space and evokes an enigmatic fusion of the real and the imagined. The paintings are imbued with radiant colours and expressive brushwork, revealing the intuitive and imaginative process of painting. The landscapes are both familiar and mysterious, encouraging the viewer to project their own narrative and context to the works, offering themselves to our imagination.

Elizabeth Magill has been focused on landscape painting for many years, and her approach is psychological and deeply subjective. Born in Canada, and raised in Northern Ireland, Magill continues to travel back to the countryside in Ireland from London where she works and resides. Photographs form the basis of her ambitious compositions, which on one level documents and monumentalises the landscapes that she is drawn to. Her technique is innovative and unique, often combining imagery from photographs, screen-printing, stencilling and collage which create complex, dense vistas that are intriguing to penetrate. In ‘Still (Revised)’, the painterly application and textures of her painting method are evocatively revealed, imbuing the scene with the expressive sense of wind and movement. This work at once celebrates the power and majesty of nature, the noble stature of the trees in centre stage. But it also hints at a fragility and vulnerability, as the forms are buffeted across the canvas. This sense of foreboding is brought to the fore in Magill’s painting ‘Fota Park Red’ – the sky is a luminous red, the surface of the canvas textured, worn and weathered. Here the stark outlines of trees emerge through the haze, there is a sense of something lost, abandoned, and in threat. The idyllic and Arcadian vision of nature is at risk, the natural world as we know it is in danger, and Magill’s epic paintings both highlight the wonder of nature, and also exposes its instability and the precariousness of the status quo.

This sense of fragility and uncertainty is beautifully executed in the Blue Hour series by Saad Qureshi. These works also explore a more profound, spiritual connection with the natural world, where historically birds become symbolic bearers of both good and bad will. Through Western mythology and in religious texts, birds were signifiers of a day of reckoning or a prophetic symbol or omen. The artist recollects his childhood in Pakistan, when his mother would chase away crows, afraid that their presence and song would bring ill fortune. If the birds were out of reach, the artist learnt to point a mirror in their direction, and this would cause them to fly away. “See”, she would tell him, “they’re even afraid of themselves”. Qureshi’s practice often draws on his rich, personal recollections and memories, which in turn inspire works that attest to the human experience. These works reveal how experiences of nature can impose deep imprints on our psyche. The scale and composition of these works appear as vignettes, snapshots or fragments of memory. By incorporating the form of the birds, these become a vehicle to express a more profound misgiving about the environment and their presence exudes a sense of apocalyptic augury that prescient climate experts are remonstrating.

Through these stark warnings we are encouraged to be mindful, present and appreciative of the significance of the natural world. Echoing Qureshi’s adoption of the bird motif to explore our profound connections with nature, Rene Gonzalez also features animal protagonists in his paintings. Gonzalez’s landscapes are imbued with a sense of reverie, imagination and a joyful celebration of the wonders of nature. Elements of classical architecture are juxtaposed with verdant landscapes of trees, flora and fauna that envelop the viewer with their illustrative detail and vibrant colour palette. Like Douglas-Morris, Rene’s scenery appears to be an amalgamation of differing terrains and landscapes. The viewer embarks on a journey through forests, architecture, the tropics and luscious floor-beds of undistinguishable woodland. Memories of childhood fairy tales and folklore are evoked, with the appearances of deer and red foxes endowed with an endearing sense of anthropomorphism. Amy Beager’s highly saturated, colourful paintings depict the human figure in leisurely pursuits, relishing in the adventure of the great outdoors, where two female figures precariously climb up a precipice, or lie contemplatively watching the rain cascade from the sky. Beager’s loose handling of paint emphasises the sense that the viewer is capturing a fleeting moment or memory, one that celebrates nature and our place within it.

Hannah Brown’s painting practice has focused on the English landscape, and how it has been reproduced and represented. Rather than portray the more conventional and idyllic vistas, Brown searches for “quiet, potentially unsettling places with a peculiar type of beauty”. Brown presents us with the glimpse of a candy-coloured sky, the crepuscular light of the sun setting over undulating hills, capturing the allure and grandeur of an Arcadian landscape of the past. The artist deliberately disguises her locations, void of any landmarks, to encourage the viewer to project their own narrative or sense of place on the scene. This picturesque vista is surrounded by a highly detailed canopy of leaves and hedgerow that provides a theatrical framework to the drama of the pink and purple hues of the twilight sky. This dense foliage creates a sense that the viewer has stumbled across a secret garden or hidden place, the leaves suggest shelter and a rather claustrophobic encroachment across the canvas, an ambiguous tension. The artist reveals that the sources of these paintings are far from the hills of the English countryside, but are in fact secluded areas of her local park in London. Brown reworks these into epic vistas that distil the artist’s experience of the landscape and reinforces the concept of nature as a refuge and a significant point of focus. The artist presents a revitalised perspective on areas of nature that can be disregarded, overlooked and undervalued; a premonitory notion that we should all take heed of.

What aligns these artists are not topographical records of the landscape or locations, but evocative, dream-like scenes that create a sense of solace, contemplation, memory and human connection.